Currently Reading No Win Race by Derek A Bardowell

I haven’t posted here for a long time as life took over in the run-up to The Reader opening Calderstones Mansion this time last year. But this morning there was time and mental space, so here I am. But as one of the world’s slowest readers, as you’ll see, I didn’t get very far!

Thanks and apologies to people who posted responses I didn’t look at – I seemed to have simply turned away from this place and completely forgotten to ever look back. I’d forgotten how to log in. But hope I have approved those comments -thanks for responding. It’s good to hear a voice at the other end!

But about Ode to Duty….

In my early relationship with Wordsworth ‘Ode to Duty’ was a poem I chose to ignore. I would skip past it because, well, duty. ‘Duty’. Pah.

I was born in 1955, when, following the massive amount of duty done in 1939-45 war, the idea of ‘something being due[1]’ was beginning to go out of fashion. By the time I was ten, the concept was almost entirely gone from the minds of children who had grown up in the war: it was the 60’s! My parents certainly didn’t instil any sense of duty in me, except maybe duty to self – I learned that adults did what pleased them. And by the time I was an adult myself, let’s say by 1975, when I was 20, and punk was emerging, ‘duty’ was a dirty word, and I was a self-pleasing adult.

So, as I began to read Wordsworth, from my mid-twenties on, I’d see this poem and ignore it. I think I read it in a class, with my Adult Ed students as part of ‘a get into poetry’ course, twenty, perhaps thirty years ago. And I read it when giving some kind of talk somewhere in Scotland, about the thing we at The Reader now call Shared Reading. At that point I had come round to the idea of ‘duty’. I’d be at least 40, maybe 50 by then and experience had changed my thinking. But I remember some vocal people in the audience really not liking it, not even being able to imagine what ‘duty’ might be or why humans might benefit from it. So certain we are self-determining and so much like me in the 1970s.

I don’t recall if I have read ‘Ode to Duty’ since that occasion.

Lately, the poem, a faded presence in the shadows at the back of my mind, has been stirring. The phrase – ‘stern daughter of the voice of god,’ rises unbidden and pretty much unwelcomed into consciousness as I am tussling with myself about doing things I don’t want to do. This fight-with-self has grown large during the Covid experience, perhaps because external demands have shrunk. The external demand of turning up at place of work and doing and being seen to do what is required of you has gone. Now there is only me to witness how much I give to my tasks, whether I’ve prepared for work, or tidied my room. I look at myself as if I were looking at someone else and see this woman needs to internalise externals, she needs habit-bones, she requires requirements. But lockdown and now not-quite-lockdown have left this jelly-like, unboned, unhabituated Jane facing her day without structure. She needs a sense of duty – something that feels external, something like habit. That, my poetry-reciting unconscious seems to be telling me, might be duty.

This morning, as I was doing what has become the daily exercise of inner-arm-wrestling-with-self, I heard the voice offering me the line ‘stern daughter of the voice of God’ and decided to listen to it, and read the poem again. Looking it up on The Poetry Foundation website and was surprised by the epigraph, which I didn’t remember from previous readings.

Jam non consilio bonus, sed more eo perductus, ut non tantum recte facere possim, sed nisi recte facere non possim”

“I am no longer good through deliberate intent, but by long habit have reached a point where I am not only able to do right, but am unable to do anything but what is right.”

(Seneca, Letters 120.10)

I’ve never read Seneca’s Letters but I know he is famous for Stoicism – the school of philosophy which advocates the cultivation of inner strength in order to build acceptance of the vagaries of fortune[2] – so I was almost alarmed by this assertion, which didn’t look stoical at all, rather unbelievably self-satisfied. How would you know? Choices are often not right or wrong but perhaps better or worse, to a greater or lesser extent cognizant of the variousness of things, more or less intelligent. So I tell myself – you can’t judge Seneca, nor Wordsworth’s use of his words, from this quotation. What’s the context? I need to read that letter and see the whole of it. You’ll find it here.

Having read that, I’m now thinking that Seneca wasn’t talking about himself as it initially seems in the epigraph, but about a human model (I don’t know why it is translated as ‘I’, because the two translations I’ve looked at[3] both have it in the third person), a model for any of us to follow:

Besides, he has always been the same, consistent in all his actions, not only sound in his judgment but trained by habit to such an extent that he not only can act rightly, but cannot help acting rightly. We have formed the conception that in such a man perfect virtue exists.

I’m reading the letter quickly, but as I rush through I notice this, which stops me:

… that perfect man, who has attained virtue, never cursed his luck, and never received the results of chance with dejection; he believed that he was citizen and soldier of the universe, accepting his tasks as if they were his orders. Whatever happened, he did not spurn it, as if it were evil and borne in upon him by hazard; he accepted it as if it were assigned to be his duty. “Whatever this may be,” he says, “it is my lot; it is rough and it is hard, but I must work diligently at the task.”

I love the idea of being a citizen and soldier of the universe! It takes me reeling back to Doris Lessing’s Canopus books, which first set me off on this long trail of my life at The Reader – it was from reading Shikasta that I began to understand and believe in the idea of ‘purpose’, which like, duty, was very out of fashion as a concept in my youth. I’m remembering a sentence from Shikasta which hit me when I first read it – haven’t the book to hand, so this is from rough memory: someone is looking at post-war generations and seeing how self-obsessed they are – ‘that something was due, and from them…(then something like, not a thought they could have…’ Need to go look it up.)

As I turn back to Seneca, I’m also struck by the idea of the belief in ‘hazard’ (by which I assume he means chance – see etymological dictionary – game of dice ) being destructive to one’s state of mind. If bad luck, unhappy events are merely hazard you are stuck with meaninglessness and undermined not simply by the bad event itself but also by the purposelessness of that chance. If the bad stuff we suffer is not seen as meaningless chance, but rather as a given task – ‘assigned to be his duty’, ‘my lot…the task’ what you get is a sense of a higher power – the one who assigns the orders, the duty. You don’t have to make this ‘god’, I tell myself, you can have the universe itself, the flow of life, as the assigner. Just get on with the job, Jane.

[1] See Shikasta by Doris Lessing

[2] This is my own definition, made up on the spot. You can find a better definition here.

[3] https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Moral_letters_to_Lucilius/Letter_120 https://archive.org/stream/Seneca/Seneca_djvu.txt

Is reading aloud 2019’s answer to mindfulness, asks Pandora Sykes in The Sunday Times this morning…

During the first year of life with her new baby, Pandora Sykes, a voracious reader, had naturally found herself taking to the sofa in the evenings with book in hand, for sanctuary, and sometimes, sanity. In this morning’s article she tells us how reading Meghan Cox Gurdon’s new book, The Enchanted Hour, which speaks of the benefits of reading aloud, and which prompted Pandora to try it for herself. (I’m just about to read it myself.) Later, Pandora and I spoke about the benefits and the oddness of reading aloud, and we talked about the pace, which can be, as she, and many natural and adept readers find, frustratingly slow.

I’d said to Pandora that the difference between an accomplished reader who is reading silently and the same person reading aloud is like the difference between going somewhere by car and going for a walk. Very frustrating, that three-mile walk, if you are trying to get to A+E in a hurry, but we’re not always trying to get to A+E. Sometimes we are walking simply for the walk, for the rhythm, the play of light, and the slow, changing perspective.

That’s one of the things that reading aloud, whether Shared Reading or not, offers. In her own experiments with reading aloud, Pandora reports,

I soon found myself feeling so moved by certain sentences that I had to stop and pause for thought.

That naturally arising pause for thought, for abstraction, daydream, is the sign that something else is happening, not the mere interchange or delivery of information, but an undetermined, creative response in ourselves. The space reading aloud affords for this response feels to me one of the reasons that it may be good for us. We are less passive when we enter that state, yet it is the very opposite of ‘driven’.

For myself, spending a lot of time reading aloud with others in The Reader’s Shared Reading groups, making this activity a shared one feels entirely natural. (Find out more about The Reader’s Shared Reading programmes here).

But there are times when I have needed to read aloud to myself. They have mostly been times of personal difficulty, when the rhythm of poetry, its structured order, seems to help give a kind of inner framework on which my feelings may be held up. For that I’d turn to old favourites, the dark sonnets of Gerard Manley Hopkins, the ‘Affliction’ poems by George Herbert.

But for someone reading The Sunday Times Style section this morning, feeling interested and wondering, could this be a good thing to add to my routine, let me recommend Angela Macmillan’s A Little Aloud with Love, prose and poetry for reading aloud to someone you love.

The two poems about love, and what we pay for love, ‘Two Poems: All the Heart?’ (page 175-6) are a good place to start your reading aloud. Whatever your state of connection to others, there will be something to recognise, to feel and think about in these two poems. Here’s the first of them, by Edna St Vincent Millay. Read it as slowly as you can, take your breaths at punctuation marks and stop for a rest at that full stop. Then read it again, slower. Find the right pace. Walk through the words. Breathe. Let the light play on the hills. Feel it.

Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

And rise and sink and rise and sink again;

Love can not fill the thickened lung with breath,

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

Even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution’s power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would.

Edna St. Vincent Millay

I had an operation on my foot on the 7th August and on the same day my son and daughter-in-law and their two children temporarily moved in with us while builders were undertaking work in their new house. ‘Temporarily’ turned out to be seven weeks. I’d been laid up in bed post-op, learned to walk around the house using crutches, achieved a walk up our road, become more-or-less mobile, got used to driving an automatic hire car (no need for your left foot) and finally was pretty much recovered by the time they moved out. High summer had become late autumn.

Though I was glad of both, that surgery and my son’s family interrupted whatever rhythms I’d had in the previous chunk of time, and during August and September my writing came to an end. The room I write in was piled high and wide with their household stuff, and crutches or no, I literally couldn’t get to my desk.

But it is not about the room. You can write anywhere, and finding flow is easy, even hard to avoid, when the impetus is strong. When I had small children of my own I would wake up early – four, five a.m. to find uninterrupted time for writing. But now it wasn’t only the clear, solitary hour I needed (and could have made for myself), but something to do with a feeling of mental space, with a need for cumulative rhythm which would bring about or allow impetus to emerge. Perhaps because of the surgery as much as the grandchildren, I couldn’t find that space, that rhythm. And perhaps something else was happening during that downtime.

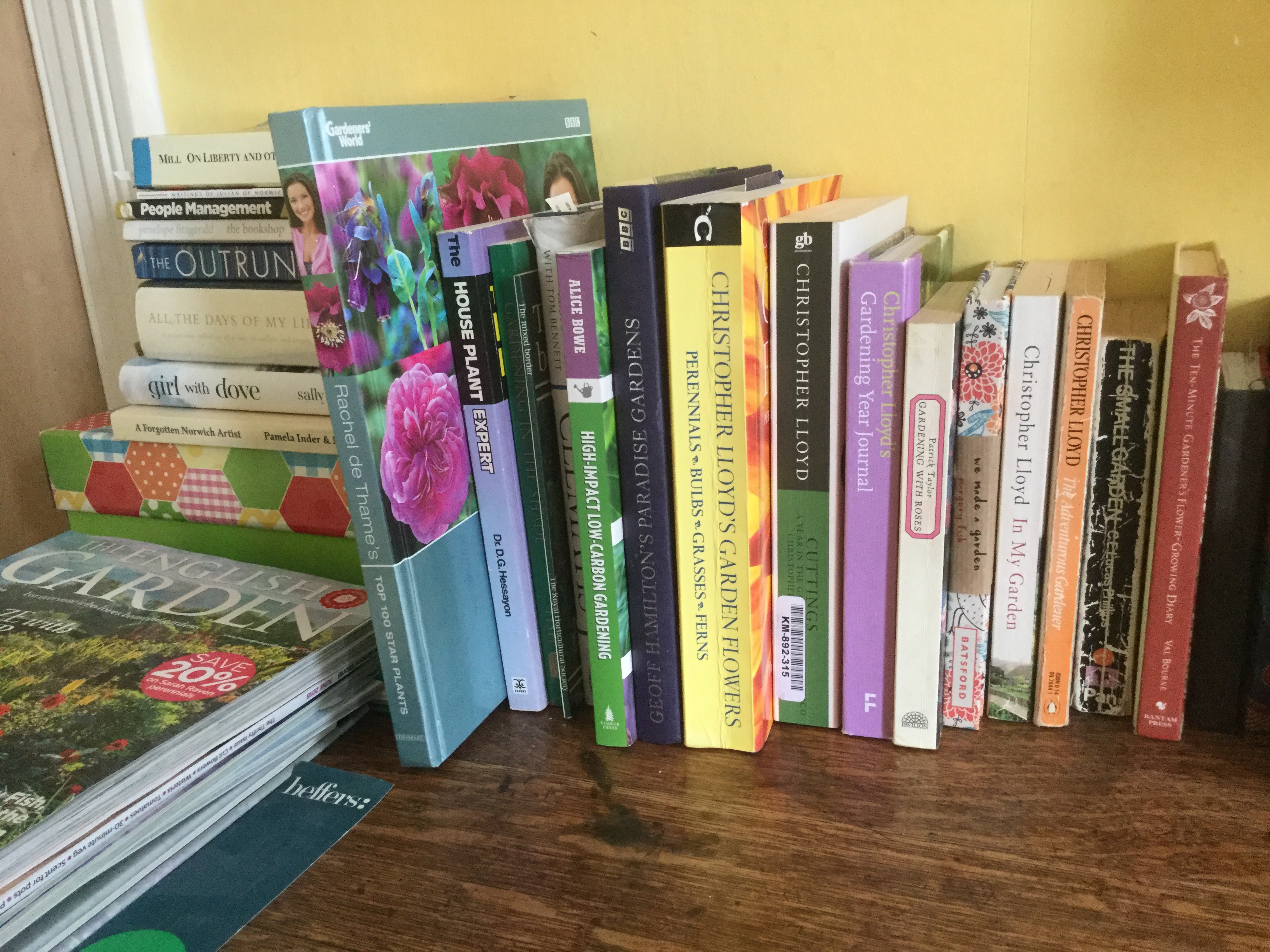

The period of recovery began with me in my bedroom, reading gardening books and being visited through the day by my temporary-resident grandchildren. They were a companionable joy with their conversations and games and stories. Then they would go off to find something more lively than me and I’d pick up my gardening book again. I say ‘reading gardening books’ as if that were a simple matter but as I think back to the first week after the surgery, on my bed with my foot raised on cushions in warm, light-washed August, I realise that ‘reading gardening books’ was a period of imaginative messing about, like the grandchildren painting or making worlds with bits of Lego or dolls in the real garden. I was mentally playing ‘gardening’.

Reading, with great attention, lists of Rachel de Thame’s favourite fifty plants, searching through my favourite specialist nursery online catalogues, I was imagining possible gardens or parts of possible gardens I might make, at some point, when not out of action and able to walk about and get down on my hands and knees with a trowel. (I’d forgotten the restriction going to work would place, has for years placed, on my gardening time, creative energy, impetus).

Short periods of concentration allowed me to enjoy short pieces of writing – stories by Nic Pizzolatto and Denis Johnson. But I didn’t seem to want fiction in the way I wanted garden writing. Was this to do with having acres of time, and it being good weather yet me being unable to get out there and do anything?

Christopher Lloyd is my favourite garden writer and I turned to him for comfort and distraction, re-reading my way through old favourites Cuttings, Garden Flowers, and Clematis. This last was one of the first gardening books I ever bought and I remember how the sense of possible obsession got to me when reading it. Yes, he openly confessed it, and I saw it was happening to me. I was beginning to adore clematis (though have struggled to grow many of them in my West Kirby sand) in the same way I had, as a beginner gardener, adored Hardy Geraniums. Am currently mildly obsessed by Euphorbias. Later, or if I ever garden on different soil, I will also adore and be obsessed by roses in exactly the same way. When I look at Rose Catalogues, I can feel that love ahead, calling to me.

What I call ‘gardening’ is more to do with such tidal obsessions, which seem to come down to the desire to note difference. A garden is whole thing, like a novel or a painting, but my gardening is more like someone collecting, and sometimes mixing, shades of paint. Happy, enchanted actually, to look at them in the paintbox. On the palette. Not painting very much. I realised early last summer when staying in an Airbnb in Stavanger that Heinrich, mine host there, had a garden. It’s a whole whole. He’s still fiddling with it but it is undoubtedly complete. Mine is not like that. I never get a finished completion, though I did once, perhaps only for a season, in the front garden, before The Reader had become the all-consuming creative love of my life. Nowadays, being unable to make time (or concentrated energy) to garden, I – so good at cutting my losses – almost don’t care about that wholeness.

What interests me most is individual plants, sometimes in combinations. I can’t get much bigger than that. And this feels – yes, this is odd – as if it may be an act of prayer or is the right word observance. I look the word up in the online etymological dictionary, which gives me a good distinction between observing and being observant.

early 13c., “act performed in accordance with prescribed usage,” especially a religious or ceremonial one, from Old French observance, osservance “observance, discipline,” or directly from Latin observantia “act of keeping customs, attention, respect, regard, reverence,” from observantem(nominative observans), present participle of observare “watch over, note, heed, look to, attend to, guard, regard, comply with,” from ob “in front of, before” (see ob-) + servare “to watch, keep safe,” from PIE root *ser- (1) “to protect.” Observance is the attending to and carrying out of a duty or rule. Observation is watching, noticing.

Observance would be the finding ten minutes a day to get out there and do something, the garden equivalent of daily prayer or meditation. Which I don’t manage, or choose to find, so I’m not observant. Yet I do love observing, watching, noticing some plants. Because I can do that with without rhythm, it’s a one-off, which I do whenever I can. This is gardening determined by no long- time rhythm.

The opposite of this would be the life of a professional, vocational plantsman or woman, a Christopher Lloyd. Read his In My Garden. Or to turn to a book I am currently reading, try this one by Clare Leighton. One of the finest engravers of the C20, she was also a gardener and her lovely book, Four Hedges (Little Toller Books), is giving me much to think about.

This morning, just after I had been writing and thinking about rhythms, I read,

From Aunt Sarah I learned the rhythm of the garden’s year. In her garden I performed those annual rituals that are necessary for happiness. I remember them as they followed upon each other through the months: I saw the first snowdrop, and plucked the first primrose. I heard the cuckoo for the first time. I listened for nightingales on May evenings. I picked a strawberry warm in the sun and climbed a ladder to gather Aunt Sarah’s apples for her. The lesser rituals would be spaced between these: watching for the first Christmas roses, the annual journey to the fritillary fields to pluck these evil, unEnglish looking flowers; the finding of bird’s nests in the coppice. It is through rituals such as these that one belongs to the earth.

‘May’ Four Hedges

I had a mainly country childhood, my grandparents knew and taught me: cuckoo-spit, lords and ladies, cleavers, goose-grass, rose-hips, blackberrying, and northern weather lore such as ‘ne’er cast a clout ‘til May is out’. I thought May meant hawthorne blossom (‘don’t bring it in the house!’ Nan would cry when I picked it) and now realise it means the month of May. Reading Clare Leighton I have been thinking of children who do not have the experience of any outdoor life or rhythm and what means for their sense of belonging. ‘It is through rituals such as these that one belongs to the earth’.

I’m also currently reading All The Little Live Things, a novel by Wallace Stegner, an American author I’ve not heard much about in the UK. This is a novel set in the 1960 or early seventies, when people like me were dropping out and tuning in. It’s a novel which has Paradise Lost in the background and asks some of the same questions: if this is nature, how did evil get in? What kind of God creates cancer? I haven’t finished it yet, so will hold my peace. But if you are looking for something chunky to read in the New Year, try one of his two great novels, Crossing to Safety and Angle of Repose, both highly recommended.

Back to time off. I had a long period of downtime. Looking back it feels like something else may have been going on during that time – something out of sight, underground. Let’s see what the spring brings.

Opening stanzas from ‘The Flower’, by George Herbert

How fresh, O Lord, how sweet and clean

Are thy returns! ev’n as the flowers in spring;

To which, besides their own demean,

The late-past frosts tributes of pleasure bring.

Grief melts away

Like snow in May,

As if there were no such cold thing.

Who would have thought my shrivel’d heart

Could have recover’d greennesse? It was gone

Quite under ground; as flowers depart

To see their mother-root, when they have blown;

Where they together

All the hard weather,

Dead to the world, keep house unknown.

#blackhistorymonth

What I am doing in this series is reading Paradise Lost, a few lines at a time, in instalments.

A quick explanation for anyone who wouldn’t naturally find themselves reading such a poem: I’m interested in acts of translation from one way of thinking to another, particularly from Christian thinking in poetry – Dante, Milton, George Herbert, Henry Vaughan and many others – to my own a-religious thoughts. Many years ago, when I wrote my Ph.D, on what I called ‘Visionary Realism’, I realised that I was interested in what happens to religious experience when people no longer believe in religion. Are there, for example, still experiences of ‘grace’? Do we ever experience ‘miracles’? Are there trials and tribulations of the soul? Is there ‘soul’? …and so on. I came into this area of thinking through Doris Lessing’s novel-series Canopus in Argos, and particularly the first novel in that series, Shikasta. There’s a partial account of this in previous blog post, ‘Lifesavers’.

You’ll find a good online text here.

Last time, (here) I was reading about how having/being a great, well-oiled, mechanical army makes you feel strong but how that strength comes at the cost of literal heart-hardening. You feel pride but not much else. Satan reviews the army/machine, his heart hardened with pride, but what do the host of fallen angels see when they look at him ?(we’re in Book 1 line 587):

Thus far these beyond

Compare of mortal prowess, yet observ’d

Thir dread commander: he above the rest

In shape and gesture proudly eminent [ 590 ]

Stood like a Towr; his form had yet not lost

All her Original brightness, nor appear’d

Less then Arch Angel ruind, and th’ excess

Of Glory obscur’d: As when the Sun new ris’n

Looks through the Horizontal misty Air [ 595 ]

Shorn of his Beams, or from behind the Moon

In dim Eclips disastrous twilight sheds

On half the Nations, and with fear of change

Perplexes Monarchs. Dark’n’d so, yet shon

Above them all th’ Arch Angel: but his face [ 600 ]

Deep scars of Thunder had intrencht, and care

Sat on his faded cheek, but under Browes

Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride

Waiting revenge: cruel his eye, but cast

Signs of remorse and passion to behold [ 605 ]

The fellows of his crime, the followers rather

(Far other once beheld in bliss) condemn’d

For ever now to have thir lot in pain,

Millions of Spirits for his fault amerc’t

Of Heav’n, and from Eternal Splendors flung [ 610 ]

For his revolt, yet faithfull how they stood,

Thir Glory witherd.

I’m thinking about real armies, or even gangs, and how when we are part of such a group, we might look at our leader. Not always with total admiration, I imagine, even if you have adopted said leader willingly. I watch. I see what he is, I know what he is. Supply your own real life leader, where you know they know they are tricking themselves but you don’t say – or even hardly dare to think in consciousness – that they are doing so. They army ‘observ’d/Thir dread commander’, where ‘observd’ is not the same as ‘looked’, or even ‘watched’ :there’s a distance and perhaps even a judgement in ‘observd’. At first we see only the leader’s strength and pre-eminence:

he above the rest

In shape and gesture proudly eminent [ 590 ]

Stood like a Towr;

But that is soon undercut by the sense of loss that attends all the fallen:

his form had yet not lost

All her Original brightness, nor appear’d

Less then Arch Angel ruind, and th’ excess

Of Glory obscur’d:

The ‘yet’ is crucial. It raises issues of time and what continues after an act. When we’ve done something wrong – imagine your own wrong thing, whatever would count as ‘sin’ or ‘corruption’. A simple time-bound act, which is completed, is one thing. (But is any act ever simply time-bound? Doesn’t everything have reverberation and consequence, ongoingness, internally even if not externally). And many other acts of wrong-doing are not, can not be, time-bound, because they affect the being of ourselves and others. In Satan’s case, he has not yet lost everything, though the ‘yet’ gives us the clue that that will inevitably perhaps happen. If you do something bad, and stop, that’s one thing. If you do something bad and continue, that’s another.

He looks like an ‘Arch Angel ruin’d’, but you still get the words ‘Arch Angel’ in a sighting him before you get to the word ‘ruind’. Something of his original state yet remains. I’m thinking of the innocence of babies and small children. They are, as Blake might have thought, innocent of experience, experience has not sullied them yet. All experience is (is it?) corrupting. I’m thinking of a speeded up film of a peach rotting – there’s corruption – it is natural, it must happen, given that we are in time, rather than in a frozen moment. The closer you are to young childhood the less sullied by experience. Is there an adult innocence which might remain unsullied? Some people do seem closer to ‘good’ than others. And when we see it, we can see what cynicism looks like and how corrupting it can be. How things unfold and continue in time matters. I believe this makes it possible for those of us who live to change, when we’ve done wrong, to do better or less wrong. If we wish. And if we can. For Satan this is never a possibility, as we will see.

Next comes a longish Miltonic simile, which you might, in a Shared Reading group, want to spend a little time on, going forward in order to look back again at what we’ve just read:

his form had yet not lost

All her Original brightness, nor appear’d

Less then Arch Angel ruind, and th’ excess

Of Glory obscur’d: As when the Sun new ris’n

Looks through the Horizontal misty Air [ 595 ]

Shorn of his Beams, or from behind the Moon

In dim Eclips disastrous twilight sheds

On half the Nations, and with fear of change

Perplexes Monarchs.

Good to get your group remembering what it looks like when mist obscures the brightness and yet lets us see the sun. Or to remember the strange cold unnaturalness of the eclipse. And to feel, that feeling e have in an eclipse does not feel good. So while Satan is upright like a tower, Milton is also undercutting him and wanting us to also feel, Satan has lost the best of himself. It’s not good. And his troops can see and feel that -remember, we started this secton with them observing him.

And now, as if a camera turned from a long panning shot of the army to a close-up of Satan, we learn how it feels to see what he sees:

Dark’n’d so, yet shon

Above them all th’ Arch Angel: but his face [ 600 ]

Deep scars of Thunder had intrencht, and care

Sat on his faded cheek, but under Browes

Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride

Waiting revenge: cruel his eye, but cast

Signs of remorse and passion to behold [ 605 ]

The fellows of his crime, the followers rather

(Far other once beheld in bliss) condemn’d

For ever now to have thir lot in pain,

Millions of Spirits for his fault amerc’t

Of Heav’n, and from Eternal Splendors flung [ 610 ]

For his revolt, yet faithfull how they stood,

Thir Glory witherd.

First we see him, from the outside:

Dark’n’d so, yet shon

Above them all th’ Arch Angel: but his face [ 600 ]

Deep scars of Thunder had intrencht, and care

Sat on his faded cheek, but under Browes

Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride

Waiting revenge: cruel his eye, but cast

Signs of remorse and passion to behold [ 605 ]

The fellows of his crime,

What a complicated picture of experience this is – however he is darkened by his loss, yet he still shines more brightly than any of his followers. I’m noticing the qualifier ‘yet’ then the next qualifier, ‘but’: even as he is brighter, he is also scarred and careworn . Now another ‘but’ –

but under Browes

Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride

Waiting revenge:

These lines are full of ‘yet’, and ‘and’ and ‘but’. Milton doesn’t want to us to say one simple thing about Satan – he wants us to see as much complexity as we can take. Including finally – and for the first time? – ‘signs of remorse’. This comes as he sees the state of his fellows:

but under Browes

Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride

Waiting revenge: cruel his eye, but cast

Signs of remorse and passion to behold [ 605 ]

The fellows of his crime, the followers rather

(Far other once beheld in bliss) condemn’d

For ever now to have thir lot in pain,

Millions of Spirits for his fault amerc’t

Of Heav’n, and from Eternal Splendors flung [ 610 ]

For his revolt, yet faithfull how they stood,

Thir Glory witherd.

The ‘yets’ and ‘buts’ and ‘ands’ are so important for building the complexity of the situation. I wonder if any of the recent world dictators/tyrants/murderers have ever felt like this – bearing the guilt of corrupting others, ruining them. How awful too to feel them both ‘faithful and yet ‘withered’. But then, does it need to be tyrant, I ask myself, could you imagine being that person? Seeing what you’ve done wrong writ large across the faces and lives of others? And of course I can.

Life after the fall is full of such misalignment, paradox, odd conjunctions, yets ands and buts. That is why I love this poem: there is no other work of literature that so strogly sets out whast it means to be fallen, me, you, the world, the lot.

If you are new to this group, welcome – it’s a reading of Shakespeare’s great play about a man who wrecks his own life and lives with the consequences. And life in various ways mends itself and comes back to him.

Look up The Winter’s Tale in the search box to get the feel of how we’re reading and what’s been happening. Find a text of the play here.

Last time, we were reading the moment when Hermione takes on the challenge of persuading Polixenes to stay longer. We’re in Act 1 Scene 2. Leontes has failed to persuade Polixenes to stay a little longer and has asked his Queen, Hermione, to try to win him. This she has done, by entreaty, gentle word play, perhaps a little flirting. We’re going to have to decide how much flirting…And we have to remember Leontes, standing near but not in the conversation, watching it unfold.

As the not-so-State-visit of the Unmentionable has unfolded before our eyes this last few days, I couldn’t help remember the play, these moments of strange cross-over between public and state affairs and the private. Look at photos of various bits of hand-holding.

But, back to the text! Let’s just read the next section:

POLIXENES

Your guest, then, madam:

To be your prisoner should import offending;

Which is for me less easy to commit

Than you to punish.HERMIONE

Not your gaoler, then,

But your kind hostess. Come, I’ll question you

Of my lord’s tricks and yours when you were boys:

You were pretty lordings then?POLIXENES

We were, fair queen,

Two lads that thought there was no more behind

But such a day to-morrow as to-day,

And to be boy eternal.HERMIONE

Was not my lord

The verier wag o’ the two?POLIXENES

We were as twinn’d lambs that did frisk i’ the sun,

And bleat the one at the other: what we changed

Was innocence for innocence; we knew not

The doctrine of ill-doing, nor dream’d

That any did. Had we pursued that life,

And our weak spirits ne’er been higher rear’d

With stronger blood, we should have answer’d heaven

Boldly ‘not guilty;’ the imposition clear’d

Hereditary ours.

HERMIONEBy this we gather

You have tripp’d since.

POLIXENESO my most sacred lady!

Temptations have since then been born to’s; for

In those unfledged days was my wife a girl;

Your precious self had then not cross’d the eyes

Of my young play-fellow.

HERMIONEGrace to boot!

Of this make no conclusion, lest you say

Your queen and I are devils: yet go on;

The offences we have made you do we’ll answer,

If you first sinn’d with us and that with us

You did continue fault and that you slipp’d not

With any but with us.

LEONTESIs he won yet?

HERMIONEHe’ll stay my lord.

LEONTESAt my request he would not.

A good example of thinking about how much you might read ahead in a Shared Reading session. I’m the world’s slowest reader, except where I need to speed up in order to show or experience the run of the action. That’s what I’d do here, speed up – because I want my group to know where we are heading – that terrible, childish, petulant line ‘At my request he would not.’

This is the point at which Leontes really begins to lose himself and his grip on reality.

I want the serious reality of this terrible moment live in the room before we go slowly through more verbal play from Polixenes. I want to get this moment in the room, because it sets an emotional tone and kind of background to what we are going to read. So, as in a poem, we’re reading not just a linear narrative but back and forth, up and down the ines.

A question someone asked me recently: how do you know when to glide over and not be too bothered about not understanding things and when to slow down and work at it?

Let’s read the opening again:

POLIXENES

Your guest, then, madam:

To be your prisoner should import offending;

Which is for me less easy to commit

Than you to punish.

This is a moment of slightly complex or hard to easily get language that anyone might think – what? Not sure what he’s just said. I’d glide here – the first line contains the real meaning: he’s going to stay. but just for interest, what does the next bit, which takes three lines, mean?

The word ‘import’ is an odd one here – one of the reasons an ear unfamiliar with Shakespearean language would or might be put off…but it just means, bring in, doesn’t it? Hhhm, not quite. Import as in suggest? To be a prisoner suggests you’ve committed an offence, that’s the import of it. I’m going to look the verb up in the good old Etymological Dictionary.

early 15c., “signify, show, bear or convey in meaning,” from Latin importare “bring in, convey, bring in from abroad,” from assimilated form of in- “into, in” (from PIE root *en “in”) + portare “to carry,” from PIE root *per-(2) “to lead, pass over.”

So that is why Polixenes speaks of a crime Hermione might punish: prisoner signifies offence.

And the next bit? A bit of harmless flirting, harmless wit, wordplay…

Which is for me less easy to commit

Than you to punish.

meaning – harder for me to commit a crime against you, than you to punish it.

But if you were looking for a hidden meaning (as Leontes, watching, may be – look at him! ) it might mean, I’d never do anything against you, but you could hurt me. It might mean that. Might not. We’ll have to wait and see. Is Leontes waiting to see?

Whatever it is, Hermione floats over this and turns the subject and lays down a line:

HERMIONE

Not your gaoler, then,

But your kind hostess. Come, I’ll question you

Of my lord’s tricks and yours when you were boys:

You were pretty lordings then?

She’s saying: I’m your hostess. That’s it. Nothing more. Tell me about your childhoods, your boyhood friendship.

I wonder about Leontes, what is he doing right now? What do we see on his face? – is this another ‘not a jar o’the clock behind what lady she her lord?’ – is she deliberately appeasing him? And that word ‘come’ implies a turning away – if you’ve got to be Hermione, on a stage, physical, are you moving at that point? Are yo taking Polixenes arm? Holding your hand out?

Oh dear times up, more next time.