Just Started

Just Started: Land of The Blind, by Jess Walter

Just Started: In The Garden, by Penelope Lively

Just Started: The Humourist by Russell Kane

Just Started

William Trevor, Last Stories

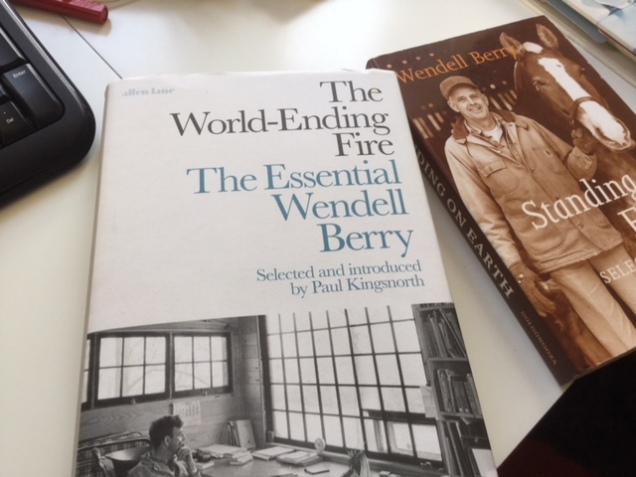

Just Started: Wendell Berry, The World-Ending Fire

I’ve been reading Wendell Berry for thirty years. Because I am narrow-minded, I often read the same things by Wendell Berry over and over again.

The poem, ‘The Slip’, which offers perspective and hope at times of loss, and which has been of practical spirit-use to me many times, would certainly be on the list if I was only allowed ten poems on a desert island.

In prose I’ve read his essay ‘The Loss of the University’ scores of times, absorbing and re-absorbing its information. I read that essay in Standing On Earth, a book every reader should own, just for that essay. Oh, let’s change everything, please. In the contemporary university, he writes,

Literature ceases to be the meeting ground of all readers of the common tongue and becomes only the occasion of a deafening clatter about literature. Teachers and students read the great songs and stories to learn about them, not to learn from them.

That simple distinction between ‘about’ and ‘from’ has been reverberating in my mind and actions ever since I first it. Over and over, I read.

I have bought Standing on Earth ten times and given it away to others.

My friend gave me this new collection – the essential Wendell Berry, edited by Paul Kingsnorth – for Christmas. Last night – aching from my weekend of hard gardening – I picked it up from the bedside table and began to read the first piece in the book, ‘A Native Hill’. I seemed to have read it before but when I checked it wasn’t in Standing on Earth. I think I might have read it at Christmas, but forgotten to write about it. Writing helps memory. How good it is to have a friend to push me out of my narrow, repetitive reading habits.

The essay is about the decision to return to Kentucky, to the place of Berry’s birth, and live there for the rest of his life. Berry wanted to be a writer. Where should a writer be in the USA? Why NYC, of course. And having got there and found the literary world, and a job at NY university, Berry changed his mind and headed back home, a move seen by some as perhaps a perverse decision and a poor career move. But back home, and a home he had chosen, as in commitment, as marriage, as planting, he found himself rooted deeper than ever before.

I began more seriously than ever to learn the names of things – the wild plants and animals, the natural processes, the local places – and to articulate my observations and memories. My language increased and strengthened, and sent my mind into the place like a live root system. And so what has become the usual order of things reversed itself with me; my mind became the root of my life rather than its sublimation. I came to see myself as growing out of the earth like other native animals and plants. I saw my body and my daily motions as brief coherences and articulations of energy of the place, which would fall back into it like leaves in the autumn.

I don’t have time to read this paragraph today. Except to note that I was profoundly moved by the thought of ‘brief coherences’ of daily action, by those ‘articulations of energy’.

That, I thought is why I long to be able to steady into habit instead of being chaotic. That is why I love gardening. I may do it in an unstructured way, but it this growing world has lots of its own rhythms, rhythms of season and structure, colour and habit, which seem to pull me into a kind of order, too.