reading aloud

Make a new year resolution to read: A Little Aloud

Is reading aloud 2019’s answer to mindfulness, asks Pandora Sykes in The Sunday Times this morning…

During the first year of life with her new baby, Pandora Sykes, a voracious reader, had naturally found herself taking to the sofa in the evenings with book in hand, for sanctuary, and sometimes, sanity. In this morning’s article she tells us how reading Meghan Cox Gurdon’s new book, The Enchanted Hour, which speaks of the benefits of reading aloud, and which prompted Pandora to try it for herself. (I’m just about to read it myself.) Later, Pandora and I spoke about the benefits and the oddness of reading aloud, and we talked about the pace, which can be, as she, and many natural and adept readers find, frustratingly slow.

I’d said to Pandora that the difference between an accomplished reader who is reading silently and the same person reading aloud is like the difference between going somewhere by car and going for a walk. Very frustrating, that three-mile walk, if you are trying to get to A+E in a hurry, but we’re not always trying to get to A+E. Sometimes we are walking simply for the walk, for the rhythm, the play of light, and the slow, changing perspective.

That’s one of the things that reading aloud, whether Shared Reading or not, offers. In her own experiments with reading aloud, Pandora reports,

I soon found myself feeling so moved by certain sentences that I had to stop and pause for thought.

That naturally arising pause for thought, for abstraction, daydream, is the sign that something else is happening, not the mere interchange or delivery of information, but an undetermined, creative response in ourselves. The space reading aloud affords for this response feels to me one of the reasons that it may be good for us. We are less passive when we enter that state, yet it is the very opposite of ‘driven’.

For myself, spending a lot of time reading aloud with others in The Reader’s Shared Reading groups, making this activity a shared one feels entirely natural. (Find out more about The Reader’s Shared Reading programmes here).

But there are times when I have needed to read aloud to myself. They have mostly been times of personal difficulty, when the rhythm of poetry, its structured order, seems to help give a kind of inner framework on which my feelings may be held up. For that I’d turn to old favourites, the dark sonnets of Gerard Manley Hopkins, the ‘Affliction’ poems by George Herbert.

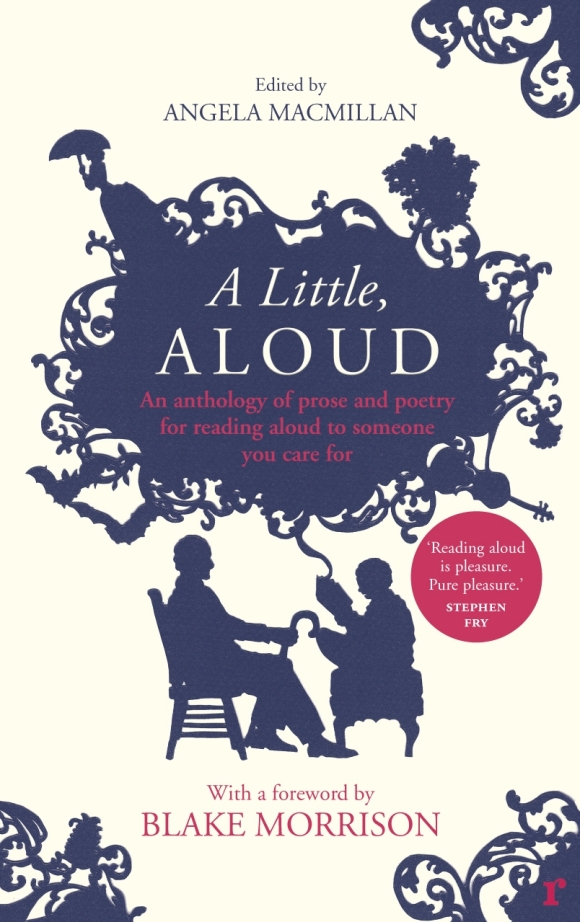

But for someone reading The Sunday Times Style section this morning, feeling interested and wondering, could this be a good thing to add to my routine, let me recommend Angela Macmillan’s A Little Aloud with Love, prose and poetry for reading aloud to someone you love.

The two poems about love, and what we pay for love, ‘Two Poems: All the Heart?’ (page 175-6) are a good place to start your reading aloud. Whatever your state of connection to others, there will be something to recognise, to feel and think about in these two poems. Here’s the first of them, by Edna St Vincent Millay. Read it as slowly as you can, take your breaths at punctuation marks and stop for a rest at that full stop. Then read it again, slower. Find the right pace. Walk through the words. Breathe. Let the light play on the hills. Feel it.

Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

And rise and sink and rise and sink again;

Love can not fill the thickened lung with breath,

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

Even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution’s power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would.

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Hurrah! Shared reading is back in fashion, according to The Observer

(First ever Get Into Reading group, St James’ Library, Birkenhead, 2002)

‘That’s true that is,’ he says. ‘That is a good.’ He looks back over the pages and runs his finger along the lines as if with fondness, and then he reads out loud, for the first time ever in this group…

yet, at the same time, now saw that there could still be many—many drops of goodness, is how it came to him—many drops of happy—of good fellowship—ahead, and those drops of fellowship were not—had never been—his to withhold.

(George Saunders, ‘10th of December’)

‘I’ve felt that,’ he says, ‘but never seen it written down before. That’s good. Never seen anyone else feeling it either but there it is.’

Elizabeth Day, a journalist with The Guardian, has been reading short stories aloud for a month at the Simon Oldfield gallery. I wasn’t at all surprised to learn of her surprise at how moving and connecting her listeners find the experience. After more than ten years of shared reading with The Reader Organisation, and an even longer 20-year backlog of reading aloud while teaching at the University of Liverpool, I know that something remarkable happens when we share our reading. Witness the story above, which concerns a man fighting for his recovery at the Drug and Alcohol centre where I run a Get into Reading group on Friday mornings. What might reading George Saunders’ terrific and terrifically moving story do for a person struggling with the conflicting tensions of a self-destructive addiction and the desire for life? I do not know, but I know that something very powerful happened when that man read those words back to us all.

(My husband Philip Davis has set up the Centre for Research into Reading (CRILS) in the School of Life Sciences at Liverpool order to work with colleagues from disciplines such as psychology, medicine, sociology and anthropology to ask big new questions about reading, and specifically reading as a shared activity. They have begun to publish some very interesting research. Perhaps one day we will develop a theory of reading which will account for those powerful moments.)

In Elizabeth Day’s group – so far as I can tell from the picture – the reader is separated from the listeners: she sits on a chair while they sit on they carpet. She does not say whether she is the only reader, but I would imagine she is… Elizabeth is reading to her group, and interestingly, she calls it ‘storytelling’, which to me suggests a strong performative element. I would imagine she reads the story all the way through, and the listeners simply listen. All well and good, and I’m glad it is happening, because one of our aims, in The Reader Organisation, is to build a reading revolution which will put books at the heart of life. Arts Galleries and addiction centres, refugee centres and retirement homes, classrooms and boardrooms. Imagine poetry being read in the Cabinet! what poems would you take along, if you were their reading group conductor?

Since I set up The Reader Organisation – more than ten years ago – we have been delivering ‘Get Into Reading’ – weekly read aloud shared reading groups in a wide variety of locations. We try to sit together, as if we were all part of the same group, usually round a table, mostly in some sort of rough circle. That said, on one memorable occasion, I read with about 60 people in Brompton Library, the group in a layered semi-circle, myself at what might have been in a musical setting, the podium. We read a marvelous short story by Eudora Welty called The Worn Path. Though it is hard for 60 people – new to each other – to form a bonded group, I think that something remarkable like that did happen that day.

But that was an unusually large shared reading group. As a rule of thumb our groups run with between 2 and 20 people and the ideal number is about 8. There is a lead reader, or facilitator, or conductor, who takes responsibility both for the reading material and for conducting, holding together, the group. That person will probably do most of the reading. But this is shared reading on a number of levels. We invite group members to join in, to take a turn at reading. No one has to read, and you don’t have to be a ‘good reader’ to take a turn. Oddly, the power of a tentative human voice, uncertain about it’s ability to read what is written, can often make the experience of sharing more, not less, powerful. I think reading aloud grows from the storytelling tradition but it is different, because reading aloud gives you language in its most complex and sophisticated form.

And because literature is complex, we at The Reader Organisation not only read, but also stop, often, to talk. The group bond partly builds through the sharing of reflections in some of the complex moments, as in the example above.

It is the double presence of the person in the words, the words in the person that is powerful.

Books to read aloud:

http://thereader.org.uk/events-and-publications/a-little-aloud/

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/jan/06/storytelling-back-in-fashion