reading

Setting off up Mount Silas

One of my readers, Orientikate, called my writing here ‘daily practice’ and I have been thinking about that.

What am I practising?

At about 1000 words a day, written in an hour or under, it’s of necessity speed writing. But I am trying to keep the reading very slow. That’s why it can take me three or four days to read a short poem. (And the speed writing explains the typos and spolling mistkaes…no time to go back over and proofread). That daily practice of concentrating hard on a few lines of poetry has been a source of deep delight for the past two months.

But yesterday I began to think about reading more than poems. Could I read Silas Marner? I am following Loubyjo’s advice, doing what I like here with no pressure, so I will make a start on Silas Marner and see what happens. If I miss the poems, I’ll stop and go back to them. Other things – book notices, reports on where I’ve been – I’m going to write at other times of the day so that this early hour remains the practice of reading and writing about the reading.

Reasons to read George Eliot even though you might be put off by the slow tone, the seriousness, the long sentences? She’s one of the most intelligent human beings ever to have put pen to paper and she has a great heart. She was a forgiving understander of human beings, and does terrific human thinking work in those long sentences. Sometimes she can be tough, literally as well as morally, but there’s a reward in taking on something tough, as anyone who has climbed a mountain knows.

So put on some stout boots, get a rucksack of provisions, and join me on this beginner’s mountain trek. I’m copying the text here from http://www.fullbooks.com/Silas-Marner1.html. I’m aiming to read about 500-1000 words of Silas each day, and I’ll drop the day’s section in a quote box. I am going to paste in the full text for today’s reading, then reading it a bit at a time. Read it aloud to start, if you can. Read it slowly, whatever you do. Just the opening two paragraphs to start:

SILAS MARNER, The Weaver of Raveloe

by George Eliot

“A child, more than all other gifts

That earth can offer to declining man,

Brings hope with it, and forward-looking thoughts.”

–WORDSWORTH.PART ONE

CHAPTER I

In the days when the spinning-wheels hummed busily in the farmhouses–

and even great ladies, clothed in silk and thread-lace, had their

toy spinning-wheels of polished oak–there might be seen in

districts far away among the lanes, or deep in the bosom of the

hills, certain pallid undersized men, who, by the side of the brawny

country-folk, looked like the remnants of a disinherited race. The

shepherd’s dog barked fiercely when one of these alien-looking men

appeared on the upland, dark against the early winter sunset; for

what dog likes a figure bent under a heavy bag?–and these pale

men rarely stirred abroad without that mysterious burden. The

shepherd himself, though he had good reason to believe that the bag

held nothing but flaxen thread, or else the long rolls of strong

linen spun from that thread, was not quite sure that this trade of

weaving, indispensable though it was, could be carried on entirely

without the help of the Evil One. In that far-off time superstition

clung easily round every person or thing that was at all unwonted,

or even intermittent and occasional merely, like the visits of the

pedlar or the knife-grinder. No one knew where wandering men had

their homes or their origin; and how was a man to be explained

unless you at least knew somebody who knew his father and mother?

To the peasants of old times, the world outside their own direct

experience was a region of vagueness and mystery: to their

untravelled thought a state of wandering was a conception as dim as

the winter life of the swallows that came back with the spring; and

even a settler, if he came from distant parts, hardly ever ceased to

be viewed with a remnant of distrust, which would have prevented any

surprise if a long course of inoffensive conduct on his part had

ended in the commission of a crime; especially if he had any

reputation for knowledge, or showed any skill in handicraft. All

cleverness, whether in the rapid use of that difficult instrument

the tongue, or in some other art unfamiliar to villagers, was in

itself suspicious: honest folk, born and bred in a visible manner,

were mostly not overwise or clever–at least, not beyond such a

matter as knowing the signs of the weather; and the process by which

rapidity and dexterity of any kind were acquired was so wholly

hidden, that they partook of the nature of conjuring. In this way

it came to pass that those scattered linen-weavers–emigrants from

the town into the country–were to the last regarded as aliens by

their rustic neighbours, and usually contracted the eccentric habits

which belong to a state of loneliness.In the early years of this century, such a linen-weaver, named Silas

Marner, worked at his vocation in a stone cottage that stood among

the nutty hedgerows near the village of Raveloe, and not far from

the edge of a deserted stone-pit. The questionable sound of Silas’s

loom, so unlike the natural cheerful trotting of the

winnowing-machine, or the simpler rhythm of the flail, had a

half-fearful fascination for the Raveloe boys, who would often leave

off their nutting or birds’-nesting to peep in at the window of the

stone cottage, counterbalancing a certain awe at the mysterious

action of the loom, by a pleasant sense of scornful superiority,

drawn from the mockery of its alternating noises, along with the

bent, tread-mill attitude of the weaver. But sometimes it happened

that Marner, pausing to adjust an irregularity in his thread, became

aware of the small scoundrels, and, though chary of his time, he

liked their intrusion so ill that he would descend from his loom,

and, opening the door, would fix on them a gaze that was always

enough to make them take to their legs in terror. For how was it

possible to believe that those large brown protuberant eyes in Silas

Marner’s pale face really saw nothing very distinctly that was not

close to them, and not rather that their dreadful stare could dart

cramp, or rickets, or a wry mouth at any boy who happened to be in

the rear? They had, perhaps, heard their fathers and mothers hint

that Silas Marner could cure folks’ rheumatism if he had a mind, and

add, still more darkly, that if you could only speak the devil fair

enough, he might save you the cost of the doctor. Such strange

lingering echoes of the old demon-worship might perhaps even now be

caught by the diligent listener among the grey-haired peasantry; for

the rude mind with difficulty associates the ideas of power and

benignity. A shadowy conception of power that by much persuasion

can be induced to refrain from inflicting harm, is the shape most

easily taken by the sense of the Invisible in the minds of men who

have always been pressed close by primitive wants, and to whom a

life of hard toil has never been illuminated by any enthusiastic

religious faith. To them pain and mishap present a far wider range

of possibilities than gladness and enjoyment: their imagination is

almost barren of the images that feed desire and hope, but is all

overgrown by recollections that are a perpetual pasture to fear.

“Is there anything you can fancy that you would like to eat?” I

once said to an old labouring man, who was in his last illness, and

who had refused all the food his wife had offered him. “No,” he

answered, “I’ve never been used to nothing but common victual, and

I can’t eat that.” Experience had bred no fancies in him that

could raise the phantasm of appetite.

Though we start off with what seems a historical novel opening, it’s worth noting the epigraph from Wordsworth before we get going.

A child, more than all other gifts

That earth can offer to declining man,

Brings hope with it, and forward-looking thoughts

This is going to be a book about the effect of a child on a declining man, a book of hope. At the beginning it doesn’t seem so, and I know a lot of people are put off by the slowness and the darkness. Wait it out. And though it looks as if it is set in the past, there will be many connections for us. Look, for example, at that unwillingness to accept strangers:

In that far-off time superstition clung easily round every person or thing that was at all unwonted, or even intermittent and occasional merely, like the visits of the pedlar or the knife-grinder. No one knew where wandering men had their homes or their origin; and how was a man to be explained unless you at least knew somebody who knew his father and mother?

We re in pre-industrial times, and the figures we see, walking to farmhouses with packs on their backs, are the sellers of fustian and other cloth, which will have been woven on hand-looms. if you’ve seen or read The Winters Tale you’ll remember Autolycus, the trickster who comes to the sheep-shearing to make a bit of money and get a girl…George Eliot reminds us that these itinerant pedlars caused suspicion among country people whose lives were unchanging from generation to generation. A small indication of the human thinking that lies ahead is given a slight fore-showing in this:

those scattered linen-weavers – emigrants from the town into the country – were to the last regarded as aliens by their rustic neighbours, and usually contracted the eccentric habits which belong to a state of loneliness.

if you are regarded as an alien by your neighbours it is very likely that you will contract ‘the eccentric habits which belong to a state of loneliness’.

I think here of lone gunmen and others who have become completely cut off from ordinary face to face life – ‘he kept himself to himself’. Eccentricity may have been more tolerated in the past? We are very much aware now, initially because of TV and red top newspapers, and latterly because of the internet, of how everyone else looks/is doing/seems. Against such strong group pressure eccentricity looks even more eccentric. But it’s interesting and sad to see that anti-social individuality was so immediately visible at the beginnings of industrialised life, and that George Eliot ascribes the root cause to loneliness.

The novel will ask us to think about loneliness and where anti-social impulses arise. Having set those thoughts gently into our minds, George Eliot now introduces us to Silas. Boys, half-afraid of the noise and machinery of his handloom, come to peer in at his cottage windows, and Silas – near-sighted – stands at the door to scare them off.

But sometimes it happened that Marner, pausing to adjust an irregularity in his thread, became aware of the small scoundrels, and, though chary of his time, he

liked their intrusion so ill that he would descend from his loom, and, opening the door, would fix on them a gaze that was always enough to make them take to their legs in terror. For how was it possible to believe that those large brown protuberant eyes in Silas Marner’s pale face really saw nothing very distinctly that was not

close to them, and not rather that their dreadful stare could dart

cramp, or rickets, or a wry mouth at any boy who happened to be in

the rear?

There’s already misunderstanding and suspicion here. the boys are part-scared, part-fascinated and part-scornful. Silas is annoyed at being interrupted. The boys frighten themselves by imagining Silas could put some kind spell on them. This thought comes partly from their parents, who regard Marner as something off a witchdoctor.

The next half of this paragraph is a bit complicated – we have to think about ‘peasantry’ – is there a contemporary equivalent? – and a complete absence of education – hard for us to imagine in our own time of universal free education? My time is up, so more tomorrow.

If You Want Escapism, Look Away Now

Yesterday I mentioned Marilynne Robinson’s Home and Joshua Ferris’ The Unnamed as examples of novels which are the kind of book I want to read. Not entertainment, and definitely not escapism. In fact, these two are the opposite, coming as close to life as it gets. Are they great books? I’m very alive while reading them, and that feels great! If the hairs stand up on the back your neck, said Les Murray, that’s poetry. That’s a sort of definition.

People often ask me about what we mean by ‘great books’ at The Reader. ‘Great’ is a relative and malleable word. Great as they may be, no books can easily be pressed on people who don’t want to read them (hence the sad state of our national literary education). So is it a canon? If so, it’s a very elastic one, decided week by week by whoever has the leadership of each group.

Our work is about passing on our love of literature, and trying to demonstrate that pwerful literature about real life is compelling and opens new areas of self (and good fun, too, a lot of the time – there’s plenty of laughing in Shared Reading). It’s not so easy to create such meaning with books that are mainly there for entertainment or escapism – no offence to them, but most murders, romances, spies, thrillers, shopping or porn stories have a different purpose. They might be ‘well written’ but it is not about ‘well written’ in the end. It’s not about technique, or ‘achingly beautiful prose’ (a phrase which makes me put down a book immediately), it’s about opening up the actual experience of human beings. If that’s happening, it might be a good book for a Shared Reading group.

We use the word ‘great’ to raise a flag for trying hard stuff. A walk in the local park is good, and beyond that, hillwalking is terrific but a trip to Everest is a completely different thing. Yet a walk in the park will be a hard task for someone who hasn’t been out in years. And walking in the Dales might be a doddle to someone who does it every weekend. Is Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451 a great book? Is War and Peace ? Is E.H. Young’s Miss Mole? What about Hamlet? Are they the same kind of ‘great’ ? No! They are all good in different ways.

I grew up with adults who were looking away. Alcohol put up reality crash barriers and felt good. Pub not sorrow. Pub a laugh! Pub not bills, not money worries. Pub borrow a few bob! Pub not dull by yourselfness. Pub jokes and laughing. Sing songs! Pub paarrty ! Or drink at home! Off licence, miniature whisky if broke. Cans of lager. Smoke dope, smoke, smoke, smoke.

This led to death, as all life does, but what I saw was that pub joy ran out while life itself ran on to the bitter end. I wanted to learn how to live differently. So the underlying flavour of my reading got serious. I’ve written about my book-turning-point, Doris Lessing’s Shikasta, elsewhere. After that came the novels of George Eliot, through my third-year university reading with Brian Nellist.

Daniel Deronda clarified things for me. I was in my mid-twenties and at a stage where decisions about the kind of person I wanted to be, the kind of life I wanted to live were more or less consciously pressing on me. I saw my self and my own existential problems in Gwendolen Harleth and in Daniel Deronda. They are very different people, but there I was in both of them…it’s a book about choices and purpose in life.

When I first read the book my mother was in her late forties and it was clear her life was coming to an end. It was a long frightening time, that approach to death. Daniel Deronda shone light on lots of things I hadn’t known how to look at, think about. The predicament of Gwendolen Harleth, forced to learn by the uncontrollable consequences of her own behaviour, terrified me into thinking seriously about the way in which I made choices.

I grew to love George Eliot and read everything she’d written, including, while I was writing my Ph.D. the nine volumes of her Complete Letters. This was (and still is) like having a parent who teaches you stuff. George Eliot helped me to grow up.

She can be hard to read – she has a rhythm that is long-sentenced and she uses complex syntax to work out complex things about human experience. Some people find the tone ponderous. I don’t. For me it is like spending time with a very clever person who knows a lot more than me. I have to keep saying, ‘Say that again!’ and I don’t understand it all, but I love being with her because I learn things.

Here’s Gwendolen (still a very young woman) at the end of the book, realising the man she loves has a bigger purpose in life than looking after her. You can’t read this stuff fast. Read it like a poem, slow and aloud.

That was the sort of crisis which was at this moment beginning in Gwendolen’s small life: she was for the first time feeling the pressure of a vast mysterious movement, for the first time being dislodged from her supremacy in her own world, and getting a sense that her horizon was but a dipping onward of an existence with which her own was revolving. All the troubles of her wifehood and widowhood had still left her with the implicit impression which had accompanied her from childhood, that whatever surrounded her was somehow specially for her, and it was because of this that no personal jealousy had been roused in her relation to Deronda: she could not spontaneously think of him as rightfully belonging to others more than to her. But here had come a shock which went deeper than personal jealousy—something spiritual and vaguely tremendous that thrust her away, and yet quelled all her anger into self-humiliation.

I wouldnt start (as I did) in the deep end with Daniel Deronda. I’d start with Silas Marner. If you read it at school and hated it (so many people did!) please give it another go. Perhaps I’ll have a look at it tomorrow.

Leaving The Eagle for A Wedding

Before the memory of Tennyson’s eagle interrupted, I had been making a start on reading Spenser’ Prothalamion. Carrying on with that today. Read the whole poem here, Get yourself back into it by reading it aloud but I’m picking up at this point;

CALM was the day, and through the trembling air

Sweet-breathing Zephyrus did softly play—

A gentle spirit, that lightly did delay

Hot Titan’s beams, which then did glister fair;

When I, (whom sullen care, 5

Through discontent of my long fruitless stay

In princes’ court, and expectation vain

Of idle hopes, which still do fly away

Like empty shadows, did afflict my brain,)

Walk’d forth to ease my pain 10

Along the shore of silver-streaming Thames,

Whose rutty bank, the which his river hems,

Was painted all with variable flowers,

And all the meads adorn’d with dainty gems

Fit to deck maidens’ bowers, 15

And crown their paramours

Against the bridal day, which is not long:

Sweet Thames! run softly, till I end my song.

The other day I’d got to ‘walk’d forth to ease my pain’ and will pick up again there.

Walk’d forth to ease my pain 10

Along the shore of silver-streaming Thames,

Whose rutty bank, the which his river hems,

Was painted all with variable flowers,

And all the meads adorn’d with dainty gems

Fit to deck maidens’ bowers, 15

And crown their paramours

Against the bridal day, which is not long:

Sweet Thames! run softly, till I end my song.

I see now (didn’t really notice before) that the lovely day bookends Spenser’s description of his own unhappy mental state, with ‘Sweet-breathing Zephyrus’ and calmness at one side, and the delightful flowery banks of the river of the other. On a quick first reading I had nearly missed his frustrated misery. The final line, which becomes a refrain for the whole poem, is a plea for continued calm, suggesting there’s still more trouble to come perhaps. But he wants to make his song in peace.

I try now to make the situation Spenser describes real to myself, I need to translate it into my own experience. I imagine this: there’s a wedding coming but you are in the middle of loads of difficulty at work – what happens? You put the difficulty aside, mentally, as best you can , and get on with celebrating the marriage. That’s what’s happening here.

The way he sees the river bank is very much in terms of wedding day – flowers, gems, maidens and their paramours and then the actual mention of a ‘bridal day’. Thinking of all these images and feelings of pleasure and sweetness crowding out his work worries. But the work worries are still there. I note them and move on.

Back to the poem, stanza two, read it aloud again:

There in a meadow by the river’s side

A flock of nymphs I chancèd to espy, 20

All lovely daughters of the flood thereby,

With goodly greenish locks all loose untied

As each had been a bride;

And each one had a little wicker basket

Made of fine twigs, entrailèd curiously. 25

In which they gather’d flowers to fill their flasket,

And with fine fingers cropt full feateously

The tender stalks on high.

Of every sort which in that meadow grew

They gather’d some—the violet, pallid blue, 30

The little daisy that at evening closes,

The virgin lily and the primrose true,

With store of vermeil roses,

To deck their bridegrooms’ posies

Against the bridal day, which was not long: 35

Sweet Thames! run softly, till I end my song.

Now I am a little perplexed. We’ve gone into fantasy or into seeing the world through the mode of classical Greece. We saw that Grecian stuff in the opening stanza but there they seems straightforward images of god-like powers – Zephyrus and Titan. What we have here are creatures, a ‘flock of nymphs’ with ‘goodly greenish locks’. I’m going to look up nymphs. (Despite what I said about the footnote killeth). Looked it up, and I go on knowing that – as I thought, a nymph is a sort of minor deity, often associated with water or specific places. My question is: are these real nymphs, with real ‘greenish’ hair, or are they figments of Spenser’s imagination – have we entered a fiction? Are they real people dressed in his imagination as nymphs? The Thames, sweet as it is, is a real river. I don’t know the answer to my question – never mind. I read on.

Each of these figures ( how many is a flock?) remind him brides:

With goodly greenish locks all loose untied

As each had been a bride;

And each one had a little wicker basket

Made of fine twigs, entrailèd curiously. 25

In which they gather’d flowers to fill their flasket,

And with fine fingers cropt full feateously

The tender stalks on high.

I’ve decided I’m treating it as a fiction. I’m in a story.

A few weeks ago here on this blog I started to think about different types of poem – direct, personal, thinking, story etc. I’m assuming this is story and so the part of me that loves narrative – what’s going to happen – is firing up now. I still have some language to untangle as lots of words seem unfamiliar and I have to keep looking up some of the Greek stuff, but I’ve stopped feeling worried. This is not beyond me. The nymphs are picking flowers for vases back at home. (Looked up flasket, nice old word). They gathered flowers

Of every sort which in that meadow grew

They gather’d some—the violet, pallid blue, 30

The little daisy that at evening closes,

The virgin lily and the primrose true,

With store of vermeil roses,

To deck their bridegrooms’ posies

Against the bridal day, which was not long: 35

Sweet Thames! run softly, till I end my song.

Had to look up ‘vermeil’ but shouldn’t have bothered ,should have just guessed. It’s vermillion! It’s a red, red rose. Which makes me think of a love poem. These girls are getting ready for a wedding – but why are ‘nymphs’ they turning into girls in my mind? They are fictions, and unreal, but they are also real. Why? Partly, the flowers, like the Thames, are real, here and now flowers, not parts of Greek mythology, partly perhaps the mention of their bridegrooms, and the bridal day – ‘which was not long’.

At the end, the stanza closes with the invocation to the Thames to ‘run softly’. Is this asking for a moment of peace? After all the Thames runs through London, where the court (his workplace?) Spenser was so frustrated in (stanza 1) is based. Let’s have this interlude, perhaps he is saying, let’s enjoy this.

I’m racing through it now.

With that I saw two swans of goodly hue

Come softly swimming down along the Lee:

Two fairer birds I yet did never see;

The snow which doth the top of Pindus strow 40

Did never whiter show,

Nor Jove himself, when he a swan would be

For love of Leda, whiter did appear;

Yet Leda was (they say) as white as he,

Yet not so white as these, nor nothing near; 45

So purely white they were

That even the gentle stream, the which them bare?

Seem’d foul to them, and bade his billows spare

To wet their silken feathers, lest they might

Soil their fair plumes with water not so fair, 50

And mar their beauties bright

That shone as Heaven’s light

Against their bridal day, which was not long:

Sweet Thames! run softly, till I end my song.

But that third stanza takes me over the days word limit. And introduces the myth of Leda and the Swan, of which I’ll remind myself before tomorrow.

A Lovely Day and Some Worries

Grandsons nos 1&2 working on something

A number of problems about writing each day are becoming clear.

First, there’s a problem about copyright which restricts my daily reading and writing. The question, dear readers, is: would you mind if I simply offered a link to a poem which you can find elsewhere ? I’d read it and think about it, and quote from it but I would not reprint it…so you wouldn’t quite have it in front of you as you read. Does that matter or not? I think it probably does.

Second, there’s the problem of long poems. I’m not suggesting a reading The Divine Comedy or The Prelude here (yet) but I’m not sure if readers got sick of, bored with my reading of Intimations of Immortality, which was spread over about two weeks.

I’d like to read some contemporary poems, and I’d like to read some long poems. So tell me what you think, please!

Meanwhile I’m going to jump the gun a little by starting a longish poem. As well as old favourites, long, short, ancient and modern, I also want to read poems that are new to me. So here is one, which I found while browsing in Palgrave’s Golden Treasury.

My third problem concerns the length of these posts. Some days I am very constrained by time but I try to have an hour for reading and writing. If that includes choosing, too, then I am definitely short on time. But I am more bothered about when I’ve got longer. I don’t want these posts to be long. I want to keep them under 1000 words. Going to try to stick to that, which will mean stopping short some days. Today probably.

So, to the poem.

I’m sorry to admit I’ve never found a clear way through to Edmund Spenser, though my great literary mentor, Brian Nellist, has always been vocal in his love for everything Spenserian. I struggled with The Faerie Queene at University and don’t think I’ve ever read it since. Brian also loves Sir Walter Scott and I’ve never happily read Scott either, so it may be that these are things particularly appealing to Brian’s personality and anti my own. But I wanted to give it another go.

I don’t know much about Spenser, and I’m interested to see if it is necessary to ‘know’. I mainly don’t want to ‘know’ things about poets or their worlds, I want to read the stuff itself, not about the stuff. For me it is a practical art and I want it to work practically, moving or enlightening or astounding me. So I’m not going to look up any facts about Spenser or the poem. I’m going to just going to read, ignorantly or innocently, a bit at a time, and see what happens. (Reserving the right to stop, or even to look up some facts if things get desperate).

Prothalamion

CALM was the day, and through the trembling air

Sweet-breathing Zephyrus did softly play—

A gentle spirit, that lightly did delay

Hot Titan’s beams, which then did glister fair;

When I, (whom sullen care, 5

Through discontent of my long fruitless stay

In princes’ court, and expectation vain

Of idle hopes, which still do fly away

Like empty shadows, did afflict my brain,)

Walk’d forth to ease my pain 10

Along the shore of silver-streaming Thames,

Whose rutty bank, the which his river hems,

Was painted all with variable flowers,

And all the meads adorn’d with dainty gems

Fit to deck maidens’ bowers, 15

And crown their paramours

Against the bridal day, which is not long:

Sweet Thames! run softly, till I end my song.

I have read Spenser’s poem about his marriage (Epithalamion) and remember that ‘epithalamion’ means something like marriage, so quickly glanced at the dictionary to see what the difference is (epi is written specifically for the bride, pro simply in celebration of a marriage). There! I am quickly past the off-putting title and into the first stanza. All’s well.

CALM was the day, and through the trembling air

Sweet-breathing Zephyrus did softly play—

A gentle spirit, that lightly did delay

Hot Titan’s beams, which then did glister fair;

If you are not a confident reader you might want to look up words that are strange to you, for security, as I did the title above. In which case, look up ‘Zephyrus’. I didn’t look that one – it’s something Greek-god-ish to do with wind, gently blowing (I assure myself and carry on) and Titan is (from the lines here) the sun, and I remember-ish from my (oh so long ago, so forgotten) study of the Classics, that the Titans were the children of the Gods.

I tell you all this so you can see I am no expert, and am just using the ragbag of stuff I’ve got in my mind already to get through the opening of the poem. I believe this is the best way to read. Get the gist, then look more closely at some of the words.

The gist here is, it is a lovely, lovely day. And our hero, Edmund Spenser, of whom we know virtually nothing, walks into view:

When I, (whom sullen care, 5

Through discontent of my long fruitless stay

In princes’ court, and expectation vain

Of idle hopes, which still do fly away

Like empty shadows, did afflict my brain,)

Walk’d forth to ease my pain

We don’t get a full stop anywhere here. I look up at the stanza, yes, it is one long sentence. But it breaks down into what in music, and on a larger scale, would be called movements. This second movement brings human discontent and mental affliction into direct confrontation with the lovely day. Spenser is still suffering whatever has been the matter, though it is hard to tell what is being referred to by ‘which’. It could be any or all of ‘sullen care’, ‘discontent’, ‘long fruitless stay’,’expectation vain’, ‘idle hopes’ – any or all of these, perhaps, but whatever it is/they are, they ‘still do fly away/like empty shadows’.

Bad feeling, that feeling of flickering discontent, things getting away from you.

My word count has got away from me – time to stop for today.

An Early Morning Walk with an Impatient Tudor Statesman during a postponed family Easter

Son-in-law John reading with Magnus

I’d like to spend a few days with Sir Thomas Wyatt. I know a few of his poems well from anthologies but have never read, never studied, him at length. That’s perhaps an odd state of affairs when one of his poems (‘My Galley, Charged with Forgetfulness’) would probably make it into a list of my top ten poems of all time, certainly into my top twenty.

Last night after I’d collapsed to bed leaving a late-postponed-Easter-houseful of children and grandchildren, I calmed myself down by reading some more of Sir Thomas’ poems here. I began to be struck how different poets not only have a certain recognisable style of writing but also a style of mind. You can tell when you are walking with Gerard Manley Hopkins, Emily Dickinson, Sharon Olds by how they feel in relation to the world, and ‘poetic style’ is only the top level of it. Reading twenty poems by Sir Thomas, I suddenly felt, Yes! This is you! This is what you are. Sometimes the syntax and thought is very hard and there’s often a particular back and forward to it. I’ll come back to some of those other poems over the next couple of weeks, but here’s one that seemed relatively simple with which to start.

I’ve only got until my ten-year old grandson Leo wakes up – after that it’s play, play, play, so forgive me if I break off abruptly.

Patience, Though I Have Not

Patience, though I have not

The thing that I require,

I must of force, God wot,

Forbear my most desire;

For no ways can I find

To sail against the wind.

Patience, do what they will

To work me woe or spite,

I shall content me still

To think both day and night,

To think and hold my peace,

Since there is no redress.

Patience, withouten blame,

For I offended nought;

I know they know the same,

Though they have changed their thought.

Was ever thought so moved

To hate that it hath loved?

Patience of all my harm,

For fortune is my foe;

Patience must be the charm

To heal me of my woe:

Patience without offence

Is a painful patience.

What tone is Wyatt thinking in here? When I first saw the word ‘patience’ I thought perhaps he was in an impatient state, trying to talk himself out of it. But as I’ve read on I began to think, perhaps he’s a very self-controlled man who is simply repeating a mantra that brings patience about. He worked for Henry the VIII, for goodness sakes! He had to be clever, a chess player, tightly self-controlled, surely?

I don’t know much about Sir Thomas (only glancing saw the Henry connection at the Poetry Foundation). I am going to read a biography, because I’ve got interested in him, but let’s set that aside for the time being and let’s wipe what I’ve said about Henry VIII. What can we tell – think – find ourselves wondering from reading this poem?

Patience, though I have not

The thing that I require,

I must of force, God wot,

Forbear my most desire;

For no ways can I find

To sail against the wind.

The word ‘patience’ is almost used as an invocation, he’s calling it up and calling on it. A modern psychologist might also say we’re seeing brain training here; you put the thought of the thing you want to flood the brain in first: everything else, whether you know it or not, is bathed in its light.

We don’t know what ‘the thing that I require’ is but because ‘require’ rhymes with ‘desire’ I think that for Sir Thomas it might be someone he is in love with. But if so, he’s in a difficult somewhat political situation ‘For no ways can I find/To sail against the wind.’ The fact that the ‘ways’ he’s tried are plural makes me think he has been working at this for some time. He’s stuck or trapped or held in check. Therefore ‘patience’ is the only thing he can do. The next stanza comes at the same problem from a different angle.

Patience, do what they will

To work me woe or spite,

I shall content me still

To think both day and night,

To think and hold my peace,

Since there is no redress.

I notice that the important pieces of information – the who, what, where and when – of this story are blanks. ‘The thing that I require’ remains an unknown, as now do ‘they’ who ‘do what they will/ To work me woe or spite’. He’s not committing anything to writing!

In the first stanza there was no ‘content’ but in this stanza he has found some, in some work or action he can perform keeping his thoughts to himself. An active verb, ‘to think’ performed actively, ‘to think both night and day’ and secretly, ‘to think and hold my peace’.

Blocked, going against the ind, surrounded by ‘they’, Wyatt yet creates a course of action and toughness of stubborn mind. That ‘both night and day’ is the determination of a fighter. In the third stanza we begin to understand some of the background to this:

Patience, withouten blame,

For I offended nought;

I know they know the same,

Though they have changed their thought.

Was ever thought so moved

To hate that it hath loved?

Hard to know if he is addressing himself in those opening two lines? Self blame? Feeling blamed by ‘they’? Is he telling himself, hold fast, you’ve done nothing wrong? Bad feeling to feel got at by people who say you’ve done wrong and even go so far as to falsely accuse:

For I offended nought;

I know they know the same,

Though they have changed their thought.

The beloved has cast him off for some offense, not real, has changed her mind. But I’m not thinking about the beloved as I read. I’m borrowing from my own experience, thinking of my working life. Thinking of people I’ve worked with in relation to whom saying to myself ‘Patience…For no ways can I find/To sail against the wind.’ That cast of mind could be useful.

Perhaps Wyatt is doing that too? in the Tudor Court, love and politics must have been horribly intertwined.

Patience of all my harm,

For fortune is my foe;

Patience must be the charm

To heal me of my woe:

Patience without offence

Is a painful patience.

The last stanza is almost prayer like – he’s calling for help, and I wonder how badly some of this is playing on his mind? ‘Of all my harm’ seems to suggest it’s playing a lot: ‘harm’ is a serious word. And ‘all’ makes it feel overpowering. ‘Patience’ if he can get it, is the answer, the cure, the ‘charm’. Does ‘charm’ make is seem more magic than cure? Yes ,it does, and as the dictionary shows, there’s also an element of incantation in charm, which is of course what he has been doing through the poem with the word ‘patience’. and it may heal. But the offense still rankles: he hasn’t done anything wrong! Still, there seems a lot at stake. Being wrongly judged always stings. But there’s a particularly unhappy disjunct between not having done anything wrong and a lot being at stake.

Patience must be the charm

To heal me of my woe:

Patience without offence

Is a painful patience.

I like it, it is worldly, grounded, no more complicated than it needs to be but complicated enough to make me think. This could be a good one for memorising. I need the odd incantation from time to time.

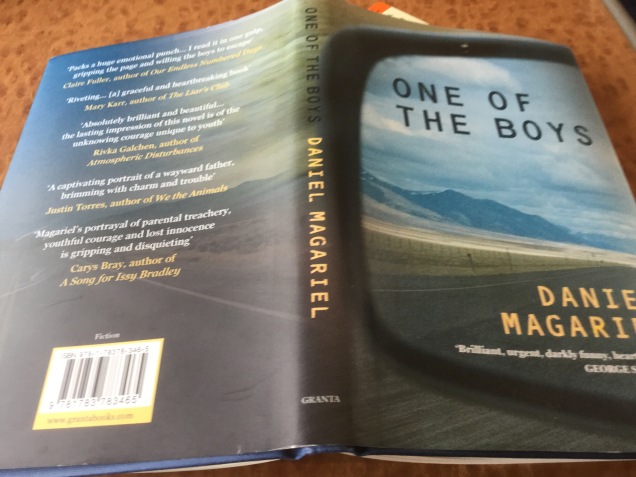

Just finished: One of The Boys, by Daniel Magariel

Yesterday a day full of addiction and hope.

I visited the wise Karen Biggs, CEO of Phoenix Futures, one of the UK’s leading addiction/housing charities. We’ve done some great work with Phoenix over the years, and it’s always a joy to spend time with the energetic heart and brain that is Karen.

Later in the day I spent time talking to playwright Sonya Hale, a truly remarkable woman. Sonya became an addict in her early twenties, and was street homeless for a decade. Much later she changed her life, partly through meeting the charity Clean Break. She won the Synergy Theatre’s national prison writing competition with her play, Glory Whispers. She spoke to me of the pain of losing her son, when her addiction became unmanageable, and he went to live with his Dad, and how that finally helped her confront her addiction and get into recovery. The interview will be published in The Reader magazine at a later date.

It was a long chat with Sonya. We’ve a lot of common and I’m always interested in learning how people live and why they sometimes learn to change. I feel as if something new has entered my bloodstream and I’ll be processing the conversation for weeks ahead.

On the train on the way down to London I finished (a two-sitting book) Daniel Magariel’s One of The Boys. I think I found this through a recommendation on twitter by the exceptionally emotionally intelligent writer, @carysbray. It also came with a blurb from my top-rated author, George Saunders. Those are two very remarkable writers, so I ordered my copy. I thought Karen or others at Phoenix might be interested in it so I when I arrived at her office in Elephant and Castle, I gave my copy to Karen Biggs.

It’s slight in terms of pages, a novella, but it is enormous in its content and concentrated experience, not unlike my two-hour conversation with Sonya. I felt I had been reading for a week, not two one-hour sessions. Reading with eyes glued to the page, full-pelt, non-stop. Told through the eyes of a child, the younger of two in a family where the father is a drug-user and is a manipulative, violent man, it’s a slice of real time, an immersion in an experience you might not want to know about. It’s not an easy read but its a real good one, with exceptionally careful writing about emotions.

The story is almost all about ‘the boys’, the father and his two sons; we don’t see the mother much and we don’t know her story, but the scene where she dances ‘salt and pepper shaker’ had a grim and utterly real graveyard humour. Apart from that, I did not laugh. I found the book frightening and true to life. Like Frank Alpine in Malamud’s The Assistant, when he is reading Crime and Punishment, I had the crazy feeling I was reading about myself.

When you have parents who do not parent you, you live a cycle of caring for them when they need looking after, craving their attention when they don’t and then suffering when they don’t look after themselves, or when they turn on you. All that is carefully detailed here, in under 170 pages.

Every care worker, every social worker or children’s home assistant, every teacher, should read this book.

Scrub that, it’s a big problem with wide ramifications. Everyone should read it.

Neither of my parents were straightforwardly ‘like’ the parents in this book but there are certain underlying resemblances, the bone structure of addiction remaining the same whatever the flesh looks like. An addict is not a grown up, is not responsible, is broken, is ill. As the child you carry a lot of weight for them. You think their thoughts, feel their feelings. As a result you never really know where your own emotions begin and your parents’ end. That’s what most struck the chimes here.

After a particularly bad night, where the father and younger son (‘we’ in the quotation below) have attacked and threatened to kill the older son, the younger struggles with guilt, anger and loneliness:

That night after we had cleaned up and dragged the coffee table to the Dumpster, my father called him into his room. I listened outside the door as he told my brother that he should never have contacted our mom. That we’d felt betrayed and did not know what else to do. “I would never hurt you,” my father said. “We only meant to scare you. Please forgive me. Do you forgive me?” Then he said, “Thank you, I forgive you, too. Can I have a hug?” The bed squeaked as my father scooted closer, I guessed, because a moment later he said, “Put your arms around me, son.”

I stepped outside to the park.

Overhead the moon was hidden. Clouds were backlit at their feathery edges. A strong wind from the east, from the Sandias, swept over the grass. I winced at the thought of today. My father turned us against each other – it was his method of control. And I’d fallen for it again. Any remorse I had for the Polaroids now felt false. I had let down my brother just as I had my mom. I was so disappointed in myself and I swore then that I would never again choose my father. I never again wanted to harm anyone I loved. I was on my brother’s side now. He was my brother for life. I’d been lucky today that he had not been not more seriously hurt.

A flock of birds came to rest on a nearby pinon tree, populating its limbs like leaves. and though I could hardly see them, hear them, I was happy for their quiet company and hoped they would not leave me soon.

Frightening, touching and educative – highly recommended.

‘You Are Tennyson’s Mouthpiece’ : a great poem by Dennis Haskell

It’s a short post today as I must get out early to catch the 7.47am London train to meet with some very interesting colleagues, supporters and potential new friends.

Yesterday I was remembering the way Tennyson’s poem, Crossing The Bar, had made me realise how powerful poetry could be once it had escaped the long-distance handling of University teaching and learning. Out of the educational context it was a different beast, dangerously alive! Of course, it always was dangerously alive for me as a private reader. And in some lectures and tutorials something powerful did happen ( I mentioned Brian Nellist, my tutor yesterday. Meet him here, but be careful, it starts with some strong swearing) but mainly, no… university tutorials were rarely the right place to share those personal experiences that made my private reading of literature so rewarding. Why? Lots of the students were too young and shy, seemed mortified, dumbstruck, or scared of losing their best ideas to someone else. They made a lot of notes but not much noise. And lots of the tutors were strange-ish folk, and seemed equally socially uneasy, some of them dumbstruck, some terrible show-offs. So University tutorials were not, on the whole, occasions on which to share one’s deepest thoughts. We kept ourselves to ourselves, or, if you were me, you talked too much and felt an idiot in a different way.

When I started ‘Get Into Reading’ in 2002, I started with years of adult education teaching behind me, and behind that, my having grown up in a pub, and having been a barmaid, a waitress. There’s a necessary human ease you have to find in those jobs, and it turns out, if you mix that barmaid and waitress, (not restricted to those professions: could be that kindly physiotherapist or creative midwife quality, or the quality of the man in B+Q who helps you find the spiggot without making you feel an idiot) with really great literature you get the most amazing firework mixture.

Over many years along with my colleagues at The Reader – both staff and volunteers – I have been amazed by the power of poetry to ‘touch’, ‘strike’, ‘move’, ‘get’ and ‘hit’ people – these interesting verbs come from readers trying to explain what is happening to them as they read.

A great poem about this effect sits alongside Tennyson’s poem in Phil’s out of print ( buy it on amazon for only 1p!) anthology, All The Days of My Life. That’s one of the great things about this book – the setting together of different poems so that they form a kind of context for each other.

I didn’t have time to write to ask permission to use it here, so you will have to go Dennis Haskell’s own site. Read it aloud. Take a tissue. I have found myself moved to tears when reading this (with the Tennyson poem alongside) in Shared Reading groups. In fact I’ve just cried now, rereading it for the first time in several years.

You’ll find Dennis Haskell’s wonderful poem, ‘One Clear Call’ here. The poem sets out what happens when the human situation really makes the words come alive in all their wild animal power.

A bit more time management, plus the Cherry, hung with snow

Three thoughts I’ve picked up on this topic which have been helpful have been (i) how slowly time would go if you were sitting on a hot stove (thanks Gay Hendricks in The Big Leap) (ii) how you’d find time to deal to deal with a flood in your house, whatever was happening at work (thanks Laura Vanderkam at TED). These thoughts are both about priorities and pain – it hurts if you don’t attend to either of them, and so they shoot to the top of the list of priorities. Time management isn’t about time so much as what matters most. You can’t do everything. Unless perhaps your name is Tim Ferris but even then… from Tim Ferris I picked up the third thought: (iii) it matters how you start your day. I used to know this once, but somehow over the last twenty years had forgotten. Writing this blog every day is helping me remember. I’m giving an hour a day to reading, and writing about a poem. That’s seven hours reading I wasn’t previously doing. This choice has made me happy (and only a little bit late on a couple of occasions).

Perhaps some of our inability to manage time comes from the refusal to accept the necessity of choice, and the subsequent inability then to act on such (unmade, perhaps unacknowledged) choices. Time management might be more helpfully called choice management. No poem does the simple sums about time, life and choices better than this, from A. E. Housman:

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

I do hope to live beyond 70, but everything now frankly feels a blessing: I know quite people of my age who have died. So I’ll stick bravely with Housman’s computation and recast it for myself: Now, of my threescore years and ten, / Sixty-one will not come again… only leaves me nine more! Ouch and aieee! Why the hell would I be doing anything that wasn’t vitally important to me? Have I seen the cherry blossom?

I run out into the garden for another look.

Last time I read this poem was in an NHS addiction service centre, sometime in the last ten years. I thought then it was a bit of a risky poem to take, given quite a lot of us in the room were over 50, and I guessed that like me, quite a few people might feel (a little) frightened by the poem, after all we’d all wasted quite a lot of time one way or another. But I thought you might only be a little frightened by the poem. And indeed, there’s something so tender and quiet in its tone, something so strong in its resolve, that no one was scared, and everyone agreed they would go for a walk and look for cherry blossom this week. Does making that choice affect one’s chances of recovery? I think every strong choice affects one’s chances.

I find the poem’s sums strengthening. You could ignore or not notice the first stanza, yeah, yeah, blossoms, again, so what. It’s a normal verse about normal blossom. you are in a normal state of mind as you read it. But the killer second stanza, quite unexpected – yet not really unexpected, is it? Because the key thing about cherry blossom is its transience, it’s there and gone. Fifty chances to see it? That’s not enough!

Time management: A Meditation Upon Flowers

Bishop Henry King’s poem has a lot of offer the contemporary blue-arsed fly.

I arrived home after nearly two weeks away in Sweden, where Spring is only just creeping into view. But here, in that short time, much has changed. The magnolia flower on my new tree has been and gone. The sweet-smelling viburnums are almost done. Much lush green stuff has sprung and the (not ornamental but fruit providing) cherry is hung with its lacy, vulnerable blossom along the bough.

Against the kitchen wall there’s a red, red rose out in flower.

All this lovely energy makes me want to garden! And I did, a little, yesterday. And to read garden books, which I did last night. And to resolve anew, ‘This year I will garden every day. Oh, every week. Oh, OK, as often as possible.’

Yes and see my children and grandchildren, and my few beloved friends, and make time to be kind to my ancient mum and to read and write every day and take exercise and eat ten portions of vegetables and makes sure I’ve done my prep for every meeting at work and I’m never going to get to a yoga class and the idea of ten minutes a day on the cello was crossed off years ago and even without those longed-for last two items my list of things is getting to the point where it begins to look undo-able.

I need to get some perspective and where I go for that perspective is Bishop Henry King. Because the tulips in my garden, the orange pointy tulips which have appeared since I went to Sweden have reminded me of his poem, a long time favourite. Brave flowers, they look, gallant and doing what they can do, putting forth in the way they can put forth. But obeying a certain discipline, too. Here they are, shining out like hearts on fire in the morning garden, and reminding me of the planting of them, which I did very late, maybe late November. I’d bought them full of good intentions and then forgotten to plant them and then found them beginning to moulder and thought, ‘What the heck, go and stick ’em in…’ And I had done so in a matter of minutes one Saturday morning in a frenzy of annoyance at myself for having forgotten to do them, but hoping they’d turn out ok, which, as I now see, they have. And the moral of this story is…

Bishop King is meditating on his own death. That makes my meditation on time management look a little trivial. But there is a relationship between the two. Part of my increasing desire for the thing I find hard to achieve – order – is to do with knowing death is coming, if not now, sometime. Like most people, for a very long time, I did not really believe that to be the case. When we are young we live – I lived – as if life was for ever, which is a good thing when you are young. But now I am not young I know that life is short, and may end sooner than you think. As far as I know there’s nothing the matter with me – nothing that being thirty years of age wouldn’t cure. But I’m not thirty, I am sixty-one. I want to make some priorities because I don’t want to die thinking I did the wrong things with my time. I wouldn’t like to die thinking I wasted it. Therefore, given the limited resource of self, priorities must be made. I am going to ask myself to get into the garden for ten minutes a day.

BRAVE flowers—that I could gallant it like you,

And be as little vain!

You come abroad, and make a harmless show,

And to your beds of earth again.

You are not proud: you know your birth:

For your embroider’d garments are from earth.

You do obey your months and times, but I

Would have it ever Spring:

My fate would know no Winter, never die,

Nor think of such a thing.

O that I could my bed of earth but view

And smile, and look as cheerfully as you!

O teach me to see Death and not to fear,

But rather to take truce!

How often have I seen you at a bier,

And there look fresh and spruce!

You fragrant flowers! then teach me, that my breath

Like yours may sweeten and perfume my death.

I love the fact that the ‘show’ the flowers make is described as ‘harmless’. The flowers. ‘brave’ and ‘gallant’ as they are, are like men in fancy royalist hats with ostrich feathers, rich velvet robes, colour. ( Have a quick look at the etymology of the word gallant here) You might call all that vain, and in humans perhaps it is so, but in flowers, no, this is not vanity: flowers are ‘harmless’. That’s quite a leap from ‘vain’ to ‘harmless’. Of course vanity can be hugely destructive, can be harmful. Humans come abroad flaunt themselves about and make a harmful mess… And when I say humans, Henry King says ‘I’.

BRAVE flowers—that I could gallant it like you,

And be as little vain!

You come abroad, and make a harmless show,

And to your beds of earth again.

You are not proud: you know your birth:

For your embroider’d garments are from earth.

It’s as if fancy clothes, those ’embroider’d garments’ (that surely Henry must have worn himself as a Bishop) are a potentially harmful show that can damage humans by causing pride and vanity. The flowers know their birth, know the ’embroider’d garments’, know they come up, and gallant it, and then go down to earth again. We tend to forget that our embroider’d garments (whatever they are, beauty, status, power, money, ego) are also as earthy and as temporally fragile. Whatever you got, it don’t last!

You do obey your months and times, but I

Would have it ever Spring:

My fate would know no Winter, never die,

Nor think of such a thing.

O that I could my bed of earth but view

And smile, and look as cheerfully as you!

The reason Bishop King meditates upon flowers is to set aside time in which to think about death. His natural inclination would be never to ‘think of such a thing.’ Therefore he has to make the equivalent of a modern day ‘to-do’ list;

1. Think abut my own death.

He has to set aside specific time to do this because, left to himself, naturally, he wouldn’t do it. Flowers are better at this than us. They are part of the natural rhythm of earth’s seasons, and they ‘do obey … months and times.’ ‘Obey’ makes the flowers subservient to a law greater than themselves but Henry King, left to himself, doesn’t want to obey such laws;

… I

Would have it ever Spring:

My fate would know no Winter, never die,

Nor think of such a thing.

The pressing, unignorable reality of being a self-willed human creature is – almost a law unto itself – and is held in place in this stanza by the double rhyme (I/die, Spring/thing are the line-ending rhymes but look how they are undercut by the internal rhyme of ‘ever’ and ‘never’). Bishop King, having set aside a little time in which to do it, tries to imagine his death, his being dead and buried, but can’t seem to even see it, and if he could see it, knows he would not be able to maintain a cheerful, gallant a brave composure;

O that I could my bed of earth but view

And smile, and look as cheerfully as you!

That’s why the mediation ends with a resolve to try to learn;

O teach me to see Death and not to fear,

But rather to take truce!

How often have I seen you at a bier,

And there look fresh and spruce!

You fragrant flowers! then teach me, that my breath

Like yours may sweeten and perfume my death.

The word ‘truce’ in the second line here is a clue to the seriousness of the problem. He’s at war with his own mortality! Does the opening line of this stanza mean that he is so afraid of Death that he cannot even see it, or that he does see it and it fills him with fear? Certainly King has seen flowers at many a funeral (the fragrance helpful in keeping the smell of mortality away). The breath that Bishop King hopes may ‘sweeten and perfume’ his death would be the breath of prayer or whatever words he might say at the end. They need to be good, strong, gallant words, not frightened battle cries. He and the flowers would be in harmony then, both in their different ways sweetening and perfuming his end.

Yes, it is a meditation on death, but I feel it is also a call to life. To ‘come abroad and make a harmless show’ in the face of mortality and time-ah running out: it asks us to go on with the show (but also know what kind of show it is.)

Thank you Bishop King, thank you, tulips.